A city in which “everything” would be accessible in less than 15 minutes on foot? The idea is seducing cities around the world, including Paris. But it is much more than a few short steps between the idea and its realisation…

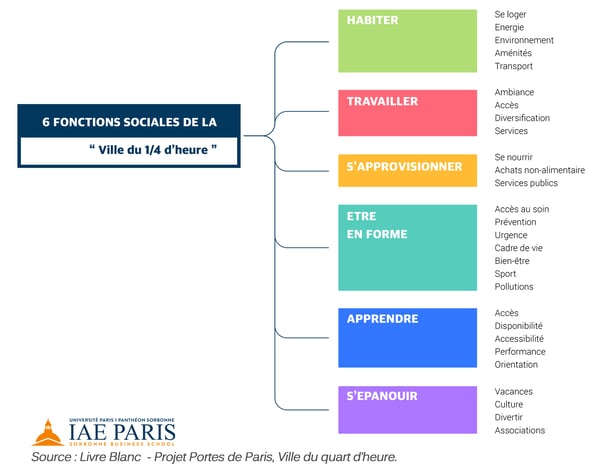

Copenhagen, Paris, Melbourne, Ottawa, Edinburgh… All these cities and many others have seized on the concept of the “quarter of an hour city” to rethink and redirect their organisation and development model. The challenge is to bring about “viable, liveable, equitable and sustainable” cities in which each inhabitant can satisfy his existential needs – living, working, shopping, learning, keeping fit, flourishing – within a one kilometre radius, a distance that everyone can cover on foot in 15 minutes.

A way out of the Covid-19 crisis?

The Covid-19 crisis, which has brought cities to a standstill and economies to their knees by drastically curtailing the movement of people, has only intensified interest in the “quarter of an hour city” and confirmed the relevance of the  on which it is based. As such it will be noted that the “quarter of an hour city” is a pillar of the post-Covid-19 recovery agenda published in July 2020 by the mayors of the C40 Cities, a network of 96 megacities totalling more than 700 million citizens around the world and committed to climate action.

on which it is based. As such it will be noted that the “quarter of an hour city” is a pillar of the post-Covid-19 recovery agenda published in July 2020 by the mayors of the C40 Cities, a network of 96 megacities totalling more than 700 million citizens around the world and committed to climate action.

This is what it has to say (pages 25-26):

“We are implementing urban planning policies that aim to promote the “15 minute city” (or “complete neighbourhoods”) as a framework for the recovery, which will enable everyone to satisfy most of their needs within a few minutes walk or bike ride from their home. This transition will be enabled by the presence of local infrastructure, such as healthcare, schools, parks, food shops and restaurants, retail outlets and essential offices, as well as the digitalisation of certain services. To achieve this in our cities, we need to create a regulatory environment that encourages inclusive zoning, mixed-use development and flexible buildings and spaces.”

The public communication campaign accompanying this recovery plan portrays quite an idealised view of the “15 minute city”.

But make no mistake: as theorised since 2014 by Carlos Moreno, co-founder and scientific director of the Entrepreneurship, Territory, Innovation (ETI) Chair at the IAE Paris – Sorbonne Business School, “the quarter of an hour city” is a long-term political approach. This approach is all the more demanding as it requires an extremely delicate rebalancing of the existing urban fabric and runs counter to decades of metropolitan policies based on individual hyper-mobility, the development of road infrastructure and the partitioning of cities into single function zones (business parks, commercial areas, recreation areas, residential neighbourhoods, business districts, etc.)

Breaking out of the industrial city paradigm

The power of theoretical models should not be underestimated, and even less so the difficulty of changing them. Today's cities are the heirs to a

born in an era of growth in which no one cared about climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, urban spread and threats to biodiversity. The Charter of Athens (1933) is often accused of being the origin of the current "urban disaster”. It is true that it laid the foundations of a functionalist urbanism that reduced the city to 4 dimensions – dwelling, work, transportation, recreation – and, above all, proposed development principles which, elevated to the status of post-war dogma, radically transformed the cityscape, especially:

born in an era of growth in which no one cared about climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, urban spread and threats to biodiversity. The Charter of Athens (1933) is often accused of being the origin of the current "urban disaster”. It is true that it laid the foundations of a functionalist urbanism that reduced the city to 4 dimensions – dwelling, work, transportation, recreation – and, above all, proposed development principles which, elevated to the status of post-war dogma, radically transformed the cityscape, especially:

- “High rise” housing, not to be aligned along main traffic routes and separated from one another to “liberate ground for large open spaces”;

- “Industrial sectors separated from residential sectors...”;

- Roads “differentiated according to their functions: residential streets, promenades, through roads, major highways”.

But the context that gave birth to these ideas and encouraged their implementation tends to be forgotten. The challenge was to address the priorities of the time: making the city compatible with industrialisation and the rapid construction of housing for the growing workforce it required. Not everything was to be abandoned under the principles of the Charter of Athens, and they did not entirely neglect the social dimension. Therefore, originally, sectoral specialisation was thought of as the way to protect housing – and thus their inhabitants – from the pollution caused by industrial activities… What is to be deplored is that the technique of “zoning” has become the dominant development mode worldwide, the consequence being:

- galloping urban sprawl, agricultural land and natural spaces retreating in the face of widespread residential and commercial development, which massively denatures the soil and makes use of the car unavoidable;

- an increasingly pronounced socio-spatial segregation, rising land and building prices, forcing the less well off ever further from the city centres and areas of employment, making them ever more dependent on individual means of transport.

The condemnation of this urban model is not recent, especially in France where the legacy of the “large housing estates” policy is particularly intractable: “Zoning is nonsense on stilts. We need employment in the city. Real diversity is functional diversity, which leads to social diversity” said architect Paul Chemetov in 2005, responding to the “neighbourhood” riots. And Christian de Portzamparc considered “that it was easy at that time [in the 1960s] to be blinded by the idea of progress. And if zoning has proved to be an act of immense folly, it was not implemented as an architectural utopia but because this functional separation was the perfect response to the economic and technical interests of the modern age.”

We should note that the French criticism of mono functionalism and the absence of social diversity applies both to the suburbs of the 1950-1960s (renamed “neighbourhoods”) and the housing fabric of the rural-urban fringe that succeeded them from the mid-1970s onwards, and which more or less equate to the “peripheral France” described by geographer Christophe Guilluy.

Transitioning from hyper-mobility to hyper-proximity

Collective priorities – and individual aspirations – have changed. Not only is no one any longer dreaming about the hyper-mobile city but by virtue of its dependence on the individual car and fossil fuels it is also completely incompatible with  . However, this city does indeed exist, and it is the city that needs to be transformed into the quarter of an hour city, into the hyper-proximity city.

. However, this city does indeed exist, and it is the city that needs to be transformed into the quarter of an hour city, into the hyper-proximity city.

The first difficulty is that the starting situations are generally very different. The central districts of Paris, for example, are already in the “quarter of an hour city” logic, with a density of public infrastructure, services, businesses and means of transport infinitely greater than is to be found in the residential areas on the outskirts of Greater Paris. The approach only makes sense at metropolitan level and aims precisely to break out of the centre-periphery dichotomy, replacing it with a polycentric city, in which each centre meets its inhabitants’ daily needs, while being better linked with neighbouring centres.

The second difficulty is that there can be no question – in terms of the 6 essential societal functions of “the quarter of an hour city”: living, working, shopping, learning, keeping fit, flourishing – of robbing Peter to pay Paul, which would only create new imbalances. It is up to the local authorities, and public authorities generally, to make full use of their powers to create the conditions for a rebalancing while working in three directions at the same time:

- recreating the local public services and infrastructure where they are missing or inadequate, while seeking the optimal location for each of them in terms of proximity and accessibility;

- implementing very proactive housing policies, access to a diversified housing offering being the key to the social diversity being sought in each centre, and playing a leading role in locating diversified businesses and services as well;

- developing a “benign” (pedestrian/cycle) traffic network within each centre/neighbourhood to render the car superfluous – which supposes intelligent connections with the rest of the road network, public transport and parking areas.

Yes, it is complicated. Above all, this requires long-term thinking, as Haussmann successfully did in his day for Paris, including the municipalities annexed in 1859. In addition to constructing new thoroughfares, Haussmann imagined and treated the city as an isotropic space, namely possessing the same characteristics in all directions. Creating all the types of infrastructure required for this new Paris to function was predicated on the principle of “distributive justice”. This expression recurs frequently in his memoirs, both in relation to schools, healthcare facilities and theatres and to networks and green spaces. Exhibiting an all too scarce concern for social fairness, this expression was for him synonymous with their homogeneous distribution throughout the city, whose duty it is to provide the same services and the same level of amenity to all neighbourhoods and social strata. This principle left a profound mark on Paris and made it, at least for those who are lucky to live and work without having to cross the ring road, a quarter of an hour city before its time.

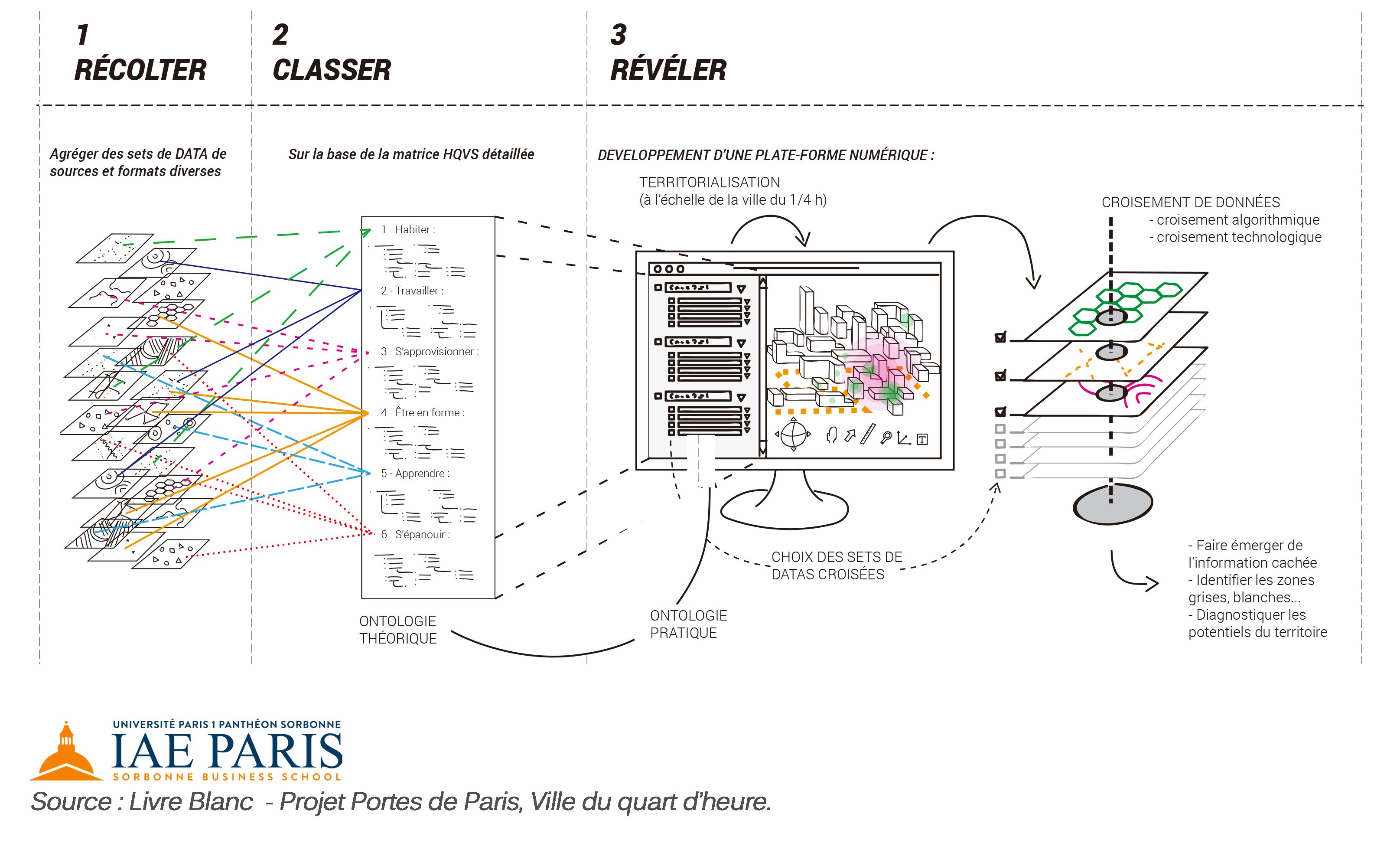

At the heart of the approach: territorial data and chrono-spatial analysis

If political will is the engine of the approach theorised by Carlos Moreno, data and spatial analysis tools are its fuel. The very tangible imperative is to understand the territory and to identify the deficiencies and imbalances one is attempting to correct, the time dimension being the key to this exploration and the required rebalancing. When one sees the number of items, for each of the 6 functions of the quarter of an hour city, for which one needs to know, or determine, the precise location, while simultaneously measuring the attractiveness, footfall, accessibility and level of use made of each place or infrastructure, one will appreciate that a “quarter of an hour city” approach is fundamentally a “data” project.

As the illustration below shows, understanding the territory, its dynamics and potential, starts with the ability to mobilise the available data. Given the diversity of formats and sources, this data gathering mechanism is necessarily accompanied by a data upgrading and structuring process.

These stages – data capture, upgrading and structuring – are the indispensable prerequisites for actually mining the data and its geographical dimension. The volumes in question and the multi-dimensional nature of the issues fully justifies the use of data mining and statistical learning techniques (machine learning and deep learning). But only spatial analysis and multi-criteria viewing and optimisation technologies – which are the very core of GEOCONCEPT’s expertise – enable “the data to speak” throughout a “quarter of an hour city” approach – whether for purposes of comprehension, exploration, simulating scenarios, decision-making or public consultation.